States of Guernsey voted to lower the voting age

Guernsey has often led the way where the mainland has later followed. Its local airline, Aurigny, was the first to ban smoking on all of its flights, and Guernsey was a whole year ahead of the mainland when it abolished the death penalty. Even then, the law had lain dormant for decades since the gruesome execution of John Tapner.

It did it again on 31 October 2007. On that day it moved to reduce the minimum age for voting in elections from 18 to 16. The proposal itself had to be voted on by the island’s Deputies, who passed the motion by 30 votes to 15. The change gained royal sanction and went into law on 19 December 2007. This required that amendments be made to the Reform Law of 1948, which governs how the island manages its elections.

Jersey had already implemented a similar change itself.

Eligibility to vote

Anyone who wants to vote has to be on the electoral roll. For this they must be ordinarily resident on Guernsey (and have been for five years overall, or the last two years consecutively) and at least 15 years old.

Voters in Herm are subject to the same conditions as those in Guernsey since the island falls within the electoral district of St Peter Port South. Sark, however, is treated separately and has set its minimum voting age at 17.

The minimum voting age in Alderney remains 18 for electing members of the States of Alderney, two representatives of which also sit in the States of Guernsey.

The first lighthouses were built on the Casquets

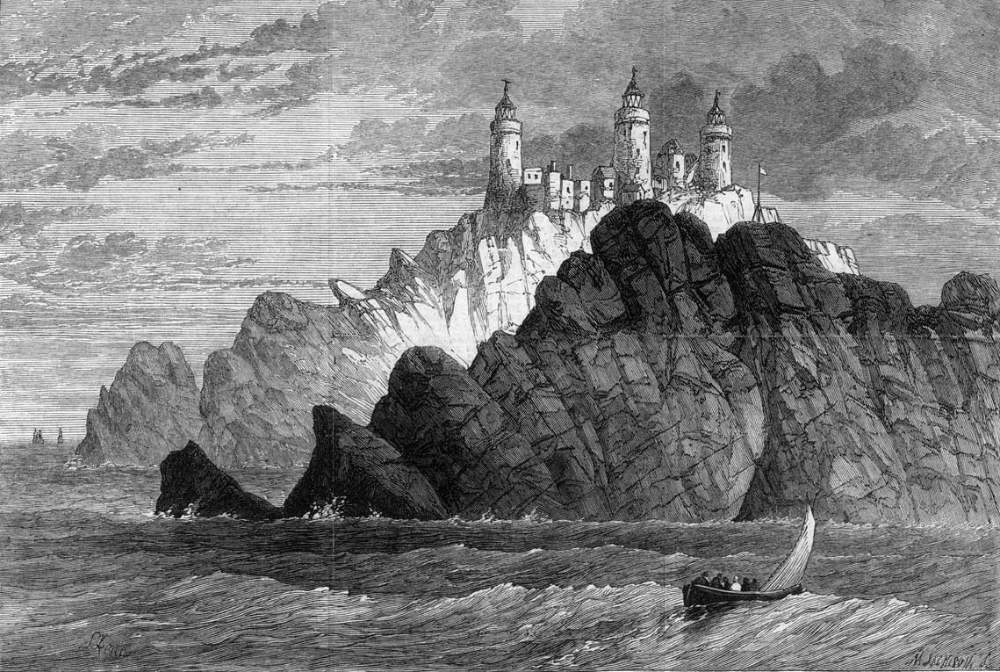

The Casquets, a series of large rocks due west of Alderney, have long been recognised as a threat to shipping. So it was that in 1724 the rocks’ owner, Thomas Le Cocq, built three lighthouses under license from the British lighthouse authority, Trinity House.

Why three rather than just one lighthouse? In order to help ships navigate, Trinity House wanted to make the lights on the Casquets distinctive so they wouldn’t be confused with those on mainland England or France. They were therefore arranged such that the lights themselves would form a horizontal triangle.

Le Cocq earned half a penny for every ton of shipping that passed by them safely. £50 of this would be sent to Trinity House in exchange for the license to operate the lights.

Called Donjon (some say Dungeon), St Thomas and St Peter, the fires on the top of each one were initially lit by coal. In 1790, five years after Trinity House had taken ownership, they were converted to oil.

Initially, they didn’t flash the way lighthouses appear to do now since there were no moving parts. However, clockwork rotating dishes were installed almost 30 years later to send out a beam across the sea. Managing these was labour-intensive as the mechanism would only run for 90 minutes before it needed to be wound up again.

Changing configuration

Today there is only one lighthouse on the Casquets, as has been the case since 1877. In that year, the westernmost tower was raised and the other two were switched off.

The remaining tower is 23m tall, putting the light 37m above mean high water when the height of the rocks is taken into account. It was electrified in 1952 and automated in 1990. Being so far off shore, it is powered by solar panels and wind turbines, which are sufficient to cast the beam of its LED lights 18 nautical miles.

Express & Star bought Guernsey Press

Guernsey Press has had several names and several owners over the years. It was founded in 1897 as the Guernsey Evening Press. In 1951 it bought the Guernsey Star and changed its title to the Guernsey Evening Press and Star.

In 1999 its publisher, The Guernsey Press Company, merged with Jersey-based Guiton, the family firm that published the Jersey Evening Post. Guiton had been one-third owned by the Wolverhampton-based Claverley Group since 1975 and, when the Guiton family wanted to sell up, Claverley Group bought the remaining shares, giving it complete ownership of both papers.

Walter Guiton

The Guiton family had become involved in newspapers just a few weeks after the Jersey Evening Post had launched. The paper had been founded by HP Butterworth, who used Walter Guiton as his printer. Seeing an opportunity, Guiton bought the title and it remained in his family until 2003.

Speaking to the BBC shortly before the sale, Guiton Group chairman Frank Walker said that there were “very heavy and strong emotional links [to the paper] not just for me but for other members of my family. We are conscious of the fact that my family has been involved in the Guiton Group since its inception…”

However, the board recognised that Claverley Group’s offer was a good one and recommended to its shareholders that they voted to accept. Guiton Group was, at the time, listed on the AIM sub-market of the London Stock Exchange. This market is where smaller companies are traded.

Claverley Group had offered 280p per share for the company, valuing Guiton at £76m. The offer represented a premium of 30% on the value of the shares at the time it made the offer.

The sale was completed the following year.

A man “disappeared” from a Guernsey ferry

Company director James “Maurice” Pitt disappeared from a steamer on its way to Guernsey on the night of 28 October 1949. Facing a charge of fraudulent conversion at Bow Street at the time, he left a note in his cabin implying that he’d killed himself. He hoped, he said, “to find peace by quietly dropping overboard”.

Pitt had been travelling on the Isle of Guernsey and had left the letter, along with his bags, in his cabin. It had been addressed to his wife and explained that he’d been motivated to take his own life because he was sick with worry. The case and letter were found with the steamer called in at Jersey.

Doctor’s note

Pitt’s lawyer had been given no notice that his client would disappear when he was supposed to be in court. The first he knew of it was when he received a letter from Pitt, which enclosed a doctor’s certificate. The certificate diagnosed a heart condition and recommended an immediate holiday.

Pitt had followed the recommendation precisely and asked his solicitor to inform the court that he wouldn’t be available for the next two weeks. The court refused to adjourn, in part because by then the certificate was almost three weeks old already.

First doubts

The day after Pitt’s abandoned case had been found on the steamer, doubts as to whether he really had gone overboard started to surface. A purser on the ship had seen a man writing a letter as they had passed the Needles, but he couldn’t say for sure it was Pitt.

In all likelihood, it wasn’t. The most probable explanation was that Pitt had boarded the ship shortly before it sailed, deposited his case and then left. His first class bed had not been slept in by the time the journey was over.

The following February, with the case still open and the Ministry of Transport unconvinced the man was dead, Pitt was at last found and arrested. The following day he was taken to Bow Street where he should have appeared five months earlier. He was remanded for eight days.

On 3 April, he was sentenced to six years’ detention after being found guilty of 15 specific instances of fraud. These included forging receipts and making false entries in his accounts.

Prison wouldn’t have been unfamiliar to Pitt. He already had 14 other convictions and had been sentenced to a total of 28 years in jail over the years. This perhaps explains why police didn’t buy into his suicide story.

Fraudulent conversion

Fraudulent conversion is the act of using someone else’s property for your own benefit, without necessarily intending to steal the property. Examples would include using somebody else’s unsecured wireless internet access or fare dodging on a train since in neither case would you be depriving the owner of the asset the ability to use it themselves.

It could also include keeping hold of something beyond an agreed return date simply because you haven’t specifically been asked to give it back. If your intention was still to return it if and when asked, rather than keep it under all circumstances, that would be conversion rather than theft.

Bailiff Sir Peter de Havilland was born

Sir Peter de Havilland, one of thirteen children, was born in St Peter Port on 27 October 1747. Sixty-three years later he was made Bailiff of Guernsey – a role that he fulfilled until his death in 1821 at the age of 73.

France and French

De Havilland was a native French speaker who spent three years in the coastal French town of Sete. There, he learned about the wine trade, but he chose not to settle upon this as his life-long career.

Instead, upon his return to Guernsey he trained as a lawyer and was sworn in at the age of 23. Unfortunately, by the time he’d turned 30 this, too, had come to an end. He was forced to resign from the law in order to sidestep the challenge of a duel.

It was now 1777 and he needed to find something else to do with his life.

Profiting from privateering

Like many of his wealthier contemporaries, he turned to privateering. Effectively waging warfare on behalf of the crown, a privateer would sink or capture enemy shipping on commission. Any ships that they captured would be sold, along with the contents, and the privateer would take a profit from the proceeds.

De Havilland himself didn’t head out to sea. Instead he invested in other privateers’ ships, thus earning himself an income without risking anything more than a little currency.

This was seen as a perfectly respectable profession at the time and it certainly didn’t harm his chances of election as a Jurat, which happened in 1785.

He invested his money in property, constructing Havilland Street, Allez Street, Sausmarez Street, Union Street and St John Street on his own land and selling plots along them to builders.

Finally, in 1810, he was appointed Bailiff and, in this position, worked with John Doyle to make sure Doyle’s proposals for building new roads to Rocquaine and Vazon were approved. As these were military roads, his support of them helped earn him a knighthood in 1817.

The de Havilland name is perhaps best known for its association with aviation. That’s because Peter’s great, great grandson was Geoffrey de Havilland, designer of the Comet and Mosquito aircraft.

GUNS founder Charles Machon died

The founders of GUNS, the Guernsey Underground News Sheet, paid a high price for their bravery. Informed upon, tried and sentenced, they were sent to prison in mainland Europe, and not all of them made it back to Guernsey alive.

One of those who paid with his life was Charles Machon, who died on 26 October 1944.

Until 2016, nobody knew for sure where his remains had been interred. However, in December it was confirmed that he had been buried in Am Wehl cemetery in the German town of Hamelin.

Machon and GUNS

Machon was a linotype operator at The Guernsey Star and Gazette when he came up with the idea of GUNS. The widely circulated publication was filled with BBC news stories that the team behind it had copied down the previous night and that morning while listening to a banned radio.

Around 300 copies of each edition were produced daily and widely circulated from hand to hand. The stories also spread by word of mouth.

Machon confessed his involvement when the German authorities threatened to arrest his mother. He was sentenced on 24 April 1944 to two years and a month of hard labour and sent, initially, to Rheinbach prison. The charges of which he was convicted were making and spreading leaflets, spreading seditious information and listening to prohibited broadcasts.

This punishment could have been enough to have killed even a strong man. However, Machon faced a more serious problem: he had a stomach ulcer. This required him to eat a special diet that simply wasn’t available in either Reinbach or Hamelin, the prison to which he was later transferred.

He died in Hamelin prison hospital, officially as a result of the ulcer. He was 51 years old.

Dame Sibyl Hathaway chose her Desert Island Discs

Not many guests on the BBC’s long-running interview strand, Desert Island Discs, can claim to actually live on an island roughly as large as the programme envisages. That makes Dame Sibyl Hathaway, ruler of Sark something of a stand-out guest.

The difference, of course, was that she didn’t live alone on Sark. Nonetheless, she said that she didn’t believe she would have trouble with the solitude of being stranded on a small patch of land in the middle of the ocean.

She appeared on the show on 25 October 1971 alongside host Roy Plomley. The Dame talked listeners through her life story. She discussed what it was like to live under German occupation and, of course, which eight records and one book she would take with her to the desert island.

Dame Sibyl’s favourite records

Her selection was perhaps not surprising in that it was almost entirely composed of classical pieces. Noel Coward’s Matelot was the only exception. Aside from him, she settled on Gershwin, Dvorak, Debussy and Mendelssohn among others.

The one record she would have saved if they were all at risk of being washed away was Symphony Number 5 in C Sharp Minor by Gustav Mahler. Why? Because, she believed, “all of one’s emotions” were tied up in it, making it the most satisfying of the lot.

Her book of choice was the History of England by Sir Keith Feiling. This would certainly have kept her occupied until rescue arrived: published in December 1950, it runs to 1264 pages.

For her luxury, she would take “lots” of canvas and tapestry tools. She would use them to weave her own Bayeux-style tapestry of the history of Sark or, if not that, the history of her own life.

The episode is still available on the BBC website. It was archived without the music, leaving just 17 minutes of interview and introduction.

Guernsey Monopoly board game went on sale

As of 24 October 2013, anyone could buy Castle Cornet, St Peter Port harbour or even Guernsey Airport – but only if they were playing Guernsey Monopoly. That was the day the localised edition of the renowned property-trading board game first went on sale.

The Guernsey variant was one of several regional editions to have been produced in the game’s long history. Other local versions include Sheffield, Carlisle and Hull.

Monopoly first went on sale in February 1935, but its history can be traced back even further – to the Landlord’s Game, developed by Elizabeth Magie in 1903.

Magie had devised it as an educational game that would teach players about the negative aspects of a monopoly developing within a market. No doubt any player who finds themselves constantly paying rent when they fall on occupied squares would be sympathetic to her aims.

Guernsey Monopoly

A number of familiar Guernsey landmarks appear around the local Monopoly board. For some reason, the Little Chapel, which is often acknowledged as the island’s most popular tourist destination, shares the lowest-value spot with the Old Quarter. It’s worth just 60 units of Monopoly currency.

At 400 units, Castle Cornet is the most expensive property, with Victor Hugo’s home on Guernsey, Hauteville House, second at 350. They occupy the positions taken by Mayfair and Park Lane on the mainland edition.

However, the game is, more specifically, a Bailiwick remake, which strays beyond Guernsey’s shores. Alderney lighthouse and railway (100 units and 200 units respectively) both make an appearance, as does the Seigneurie and Coupee on Sark. Belvoir Bay, worth 120 units and Shell Beach (220 units) represent Herm.

The game was produced by Winning Moves.

Sir Charles Hayward buys Jethou for £91,000

Sir Charles Hayward bought the lease of Jethou in October 1971. The 44 acre island had been put up for auction by Susan Faed and her husband Angus. Their family had lived on Jethou since 1964. However, anyone who had expected a session of extended bidding might have been disappointed. The whole process was completed in less than five minutes.

As one of three interested parties, Hayward initially visited the island to view the estate. It was being offered for sale at £40,000, with an additional £5,000 asked for its contents. In the end, it actually went for more than twice that amount: £91,000. He and his wife, Elsie, initially asked to remain anonymous. They didn’t move onto the island for two full years after completing the legal process of the sale in December 1971.

Sir Charles Hayward’s death

Sir Charles Hayward died on Jethou aged 90 on 3 February 1983. He was survived by his wife Lady Elsie Hayward. She put Jethou back on the market for offers over £500,000 in June; four months after Sir Charles’ death. It was bought in February the following year by a new tenant who, as the Haywards had initially done, chose to remain anonymous.

The desalination plant opened

Guernsey’s ability to produce its own fresh water received a significant boost on 22 October 1960. That was the day that the Right Honourable R A Butler, the Secretary of State for the Home Department (effectively the British Home Secretary) opened the seawater distillation plant at La Hure Mare, Vale. It was capable of distilling 80,000 gallons of seawater into 20,000 gallons of raw water every hour.

A facility like this was particularly important on an island such as Guernsey, which still relied on agriculture – and tomato exports in particular – for a portion of its income.

In 1960, Guernsey had 1,100 acres of greenhouses, all of which needed a steady and reliable source of fresh water. It could store around six months’ supply in its various reservoirs – around 500 million gallons – which would be enough to see it through a dry summer. However, this left it highly reliant on further rainfall at the end of the growing season to prepare for the next run of crops.

The economics of water

The contract to supply and build the distillation plant was put out to tender. The winning contractor, G & J Weir Ltd, calculated that equipment costs would be £257,000 and running costs would stand at around £32,000 per annum. This took into consideration the prevailing fuel costs and an anticipated use of 2000 hours a year. That equates to an average of five and a half hours per day.

The oil-fired plant was built on a half-acre site close to Juas Quarry. Juas remains one of Guernsey Water’s largest storage reservoirs, able to hold 120 million gallons. The plant worked by using heat to boil off sea water. The water condensed and was captured, leaving the salt behind.

Initially, it proved to be a great success but ultimately proved uneconomical. Within 10 years, had been abandoned in favour of traditional above-ground water storage facilities, particularly in the island’s quarries.